STEP SIX: PLOT & FRAMES

Now that when we know the who, where, when of your story, we need to know what actually takes place. What are the plot points of your campaign story? How are you framing the story? What is the nature of the conflict or question at the heart of your story? These are some of the foundational questions we will tackle in this section.

WHAT

To identify the conflict that’s driving your story, ask: What does your protagonist want? What’s preventing them from having it? And who or what is standing in the way?

Maybe in your story an island community desires safety and stability as sea levels rise around them, or maybe a city surrounded by coal plants yearns for clean air. What will the people do and say to fulfil their desires? How will they face the obstacles to their goals? The story’s conflict comes when desires clash with obstacles.

It’s important to keep your conflict as simple as you can while still accurately portraying the truth of the situation. The more time you need to explain it, the more likely you are to lose your audience. Thankfully, many conflicts can be described in terms of opposites. Just as storms are formed when a warm air mass meets a cold one, conflict is generated when two opposing qualities clash with each other. So what primary quality does your protagonist represent? How about your antagonist? Here are some possible dichotomies to get you started:

- Moral/Immoral

- Dirty/Clean

- Gentle/Ruthless

- Brave/Cowardly

- Faithful/Fickle

Weave the appropriate conflict through the fabric of your story. While the specifics of your situation are local, the values that underpin the conflict are likely to be universal. Make these values explicit. Your audience doesn’t need to know the intricacies of your issue to know the difference between what is moral and what is immoral. Expressing your conflict in those terms will help audiences understand it, and to feel invested in its outcome.

RELATED CASE STUDY

Want to see how an activist has successfully crafted her conflict with Shell? Check out this case study.

HOW & WHY

Characters provide the “who” of your story. Conflict gives you the “what,” and setting offers the “where.” With the plot, you answer the questions of “how” and “why.” A plot consists of the individual events that make up your narrative—its “how”—and a causal connection that tells you “why” they happened. That connection is important. It’s the thread that ties your story together.

“The king died, and then the queen died” isn’t a plot; it’s just two separate events. A plot might be: “The king died, and then the queen died of grief.” The specific events are linked by that all-important “why.”

The specifics of your plot will depend on the specifics of your story, but there are some durable plot structures that have endured through the centuries. Deciding on one that corresponds to your narrative can help to structure and streamline the story. Some examples:

- The Quest — The protagonist goes in search of something: an object, an ally, wisdom, etc.

- The Rivalry — The protagonist takes on an evenly-matched antagonist.

- The Underdog Tale — A “David and Goliath” story, where a plucky protagonist seeks to beat the odds and overcome a stronger antagonist.

- Temptation — The protagonist is tempted to stray from their ideals by an outside force.

- Maturation — The protagonist learns lessons as they come of age.

These are just a few of the archetypal plots that can help you to shape your story. For more examples, check out this guide from Writer’s Digest. And to see how Greenpeace storytellers have used an archetypal plot to get their message across, check out the case study below.

Using Narrative to Cultivate Supporters and Allies

Activism is not a night at the opera with the audiences in the balcony applauding the action onstage. As activist storytellers, we don’t want a passive and polite audience. We want people to engage, to become characters in our narrative and help determine how it unfolds. In fact, it is helpful to think of your audiences and supporters less as an audience and more as a community of collaborators.

Every plot point in your story should have a corresponding action point for your supporters. With each step forward, you can provide an online or IRL opportunity for them to join in with the narrative. Let them know that the story’s outcome depends on their decisions. Will it end in triumph or disappointment? Only they have power to decide.

RELATED CASE STUDY

See how Greenpeace storytellers have used an archetypal plot to get their message across in this case study.

FRAMES

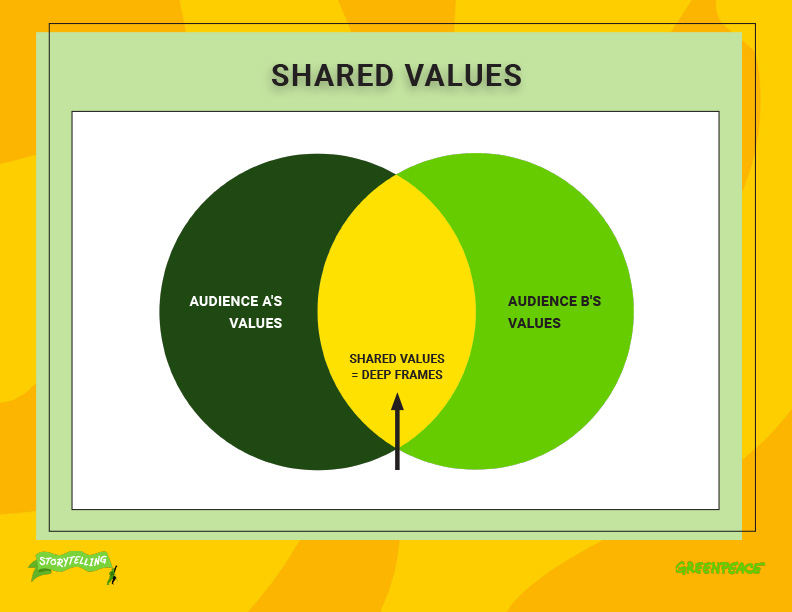

Any issue can be looked at from multiple perspectives. Take climate change, for example. It’s clearly an environmental issue, but we could also see it as a human rights issue, a security issue, a moral issue and an economic issue. When choosing how you want to portray it, you are choosing a frame. A frame is the lens through which you are representing an issue, and it has great power to shape your audience’s understanding.

Frames already exist within the collective psyche of your audience. You don’t need to create them from scratch. Instead, it’s your job as a storyteller to tap into pre-existing frames and harness their power. Frames aren’t neutral; they are intricately linked to values. So, ask yourself: What do your audiences care about most? What are their driving beliefs? Fairness? A healthy future? A safe and stable world? Cultural traditions? Whatever it is, find a way to tie the specifics of your story to what they already value.

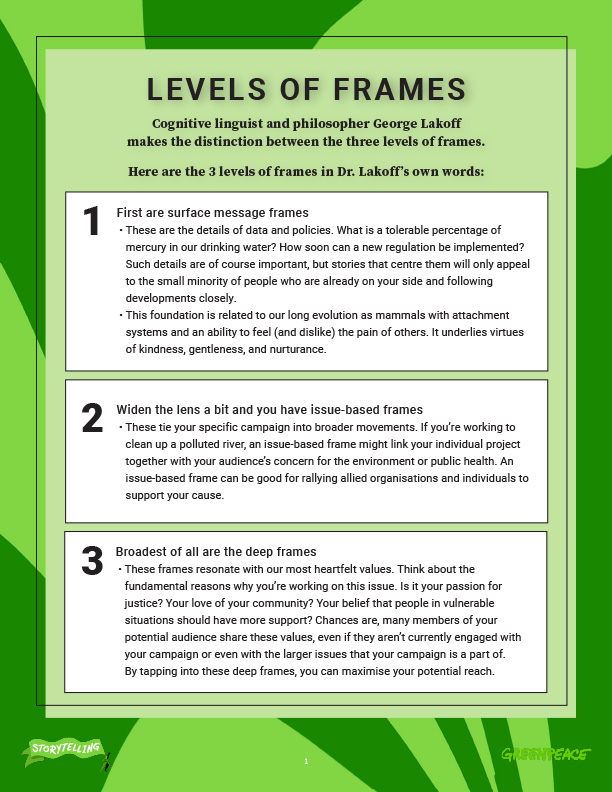

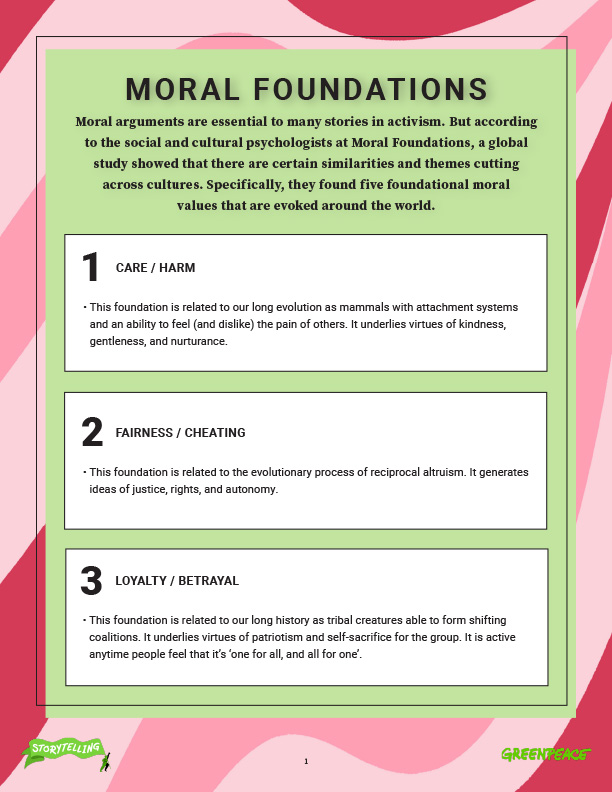

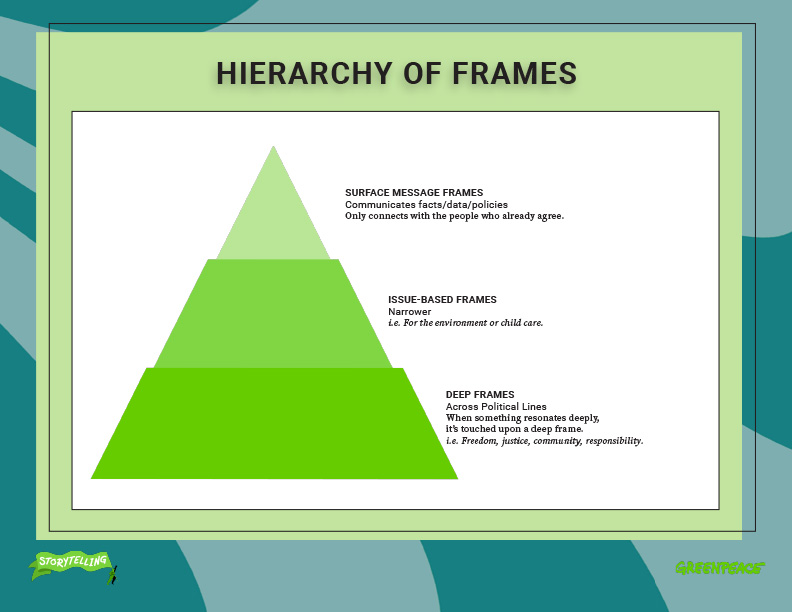

As argued by Professor George Lakoff, it’s helpful to think of frames of existing on three different levels:

- First are surface message frames. These are the details of data and policies. What is a tolerable percentage of mercury in our drinking water? How soon can a new regulation be implemented? Such details are of course important, but stories that centre them will only appeal to the small minority of people who are already on your side and following developments closely.

- Widen the lens a bit and you have issue-based frames. These tie your specific campaign into broader movements. If you’re working to clean up a polluted river, an issue-based frame might link your individual project together with your audience’s concern for the environment or public health. An issue-based frame can be good for rallying allied organisations and individuals to support your cause.

- Broadest of all are the deep frames. These frames resonate with our most heartfelt values. Think about the fundamental reasons why you’re working on this issue. Is it your passion for justice? Your love of your community? Your belief that people in vulnerable situations should have more support? Chances are, many members of your potential audience share these values, even if they aren’t currently engaged with your campaign or even with the larger issues that your campaign is a part of. By tapping into these deep frames, you can maximise your potential reach.

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS

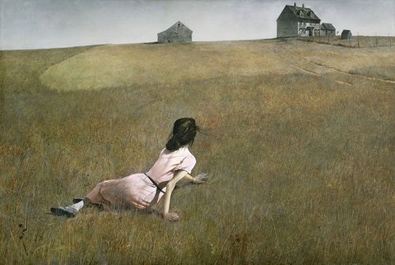

This taps into allegory or metaphor, into memories and deeply embedded narratives. This has to be done with care and recognition of the symbol’s historical and cultural meanings.

Consider what are iconic images, paintings, symbols in your narrative landscape and for your audience. Can you reference these symbols in your storytelling?

*New symbols can emerge quickly i.e. Shepard Fairey’s posters. Which he has since recast for many uses.

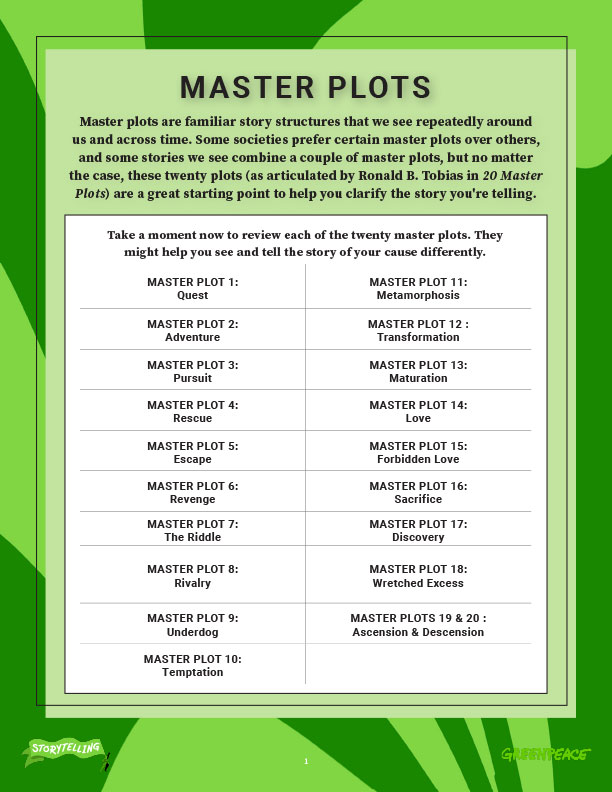

TAP INTO MASTER PLOTS

Master plots are stories that are already very common. Think of a typical hero’s journey or a romance movie. These kinds of stories are based on formulas that are familiar to many people. When you tap into these kinds of formulas, recognize that people have expectations for how the story will progress. Whether you fulfil them or not, people can often enter such stories with greater ease.

Activist movements have often told Rescue stories which have three types of characters: a Hero, a Victim, and a Villain. The Victim is the least important character in this situation. We want to avoid telling these kinds of stories because they often support problematic and disempowering narratives about “victims.” What master plots might help guide how you tell your story?

Here are some Master plots from 20 Master Plots and How to Build Them by Ronald B Tobias.

TAP INTO POP CULTURE

What popular culture matters right now? How can we recast them to shine light onto our cause? What artistic representations in museums and galleries can we recast?

Examples:

British art collective Kennard Phillipps

MAKE THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE

An oldie but a goodie. We take what’s not seen/seeable and bring it to the light.

This is what Greenpeace’s founders did when they took the world to the edge of Alaska, sailing towards a tiny island that was about to be blasted by a nuclear bomb. Through these brave women and men, we got to learn about a part of the world that many of us would never have known existed. Greenpeace continues to make the invisible visible today through the campaigning work of its ships.

REFRAME

Metanarratives are tricky. The more that you struggle against them, the stronger they get. Most of the time, challenging one of these stories directly will only work to reinforce it. Remember, metanarratives entrench themselves through decades of repetition. Argue against them directly, and your audience may respond with defensiveness and even anger. Nobody likes to be told that everything they know is wrong!

So rather than dismantle the old narratives, it’s better to reframe your perspective in a way that already fits in with your audience’s worldview. What does your audience value? Justice? Community? Creativity? A clean and safe future for the next generation? Find a way to connect your issue to the stories and ideas they already believe in, and your campaign stands a much better chance of succeeding.