LEARNING MATERIALS

Exercises, handouts, and case studies to build powerful stories.

A VIVID DREAM

Activism is hard work. With all of the daily responsibilities that go into running a successful campaign, it’s easy to lose sight of what we’re ultimately aiming for. Let’s take a minute to consider the big picture.

AUDIENCE UNDERSTANDING

A story that moves one person to tears may leave another rolling their eyes. Different characters, plots and conflicts resonate with different communities, so it’s crucial that you know who it is you’re talking to.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

In Plato’s Gorgias, Socrates argues that rhetoric, or the art of persuasion, is not a science based on general principles. Instead, we need to fully understand the cultural context in which we’re operating.

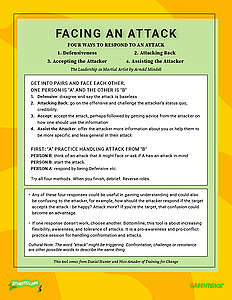

FACING AN ATTACK

Attacking your reputation, opinions and ideas is a common way opponents might attempt to diminish your impact. But an attack can also be an opportunity to be strategic and further your campaign goals.

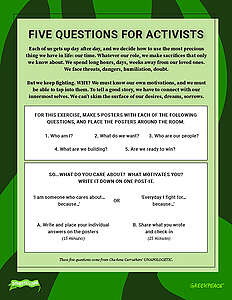

FIVE QUESTIONS FOR ACTIVISTS

Mastering how to speak about your motivations and not only what you stand for but why is a key tool for being able to tell a good story and make your campaign connect to and inspire others.

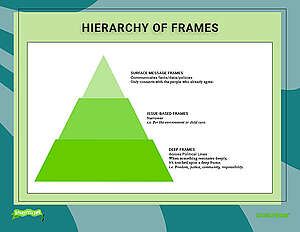

LEVELS OF FRAMES

Cognitive linguist and philosopher George Lakoff makes the distinction between three levels of frames.

MASTER PLOTS

Master plots are familiar story structures that we see repeatedly around us and across time. Some societies prefer certain master plots over others, and some stories we see combine a couple of master plots, but no matter the case, these twenty plots (as articulated by Ronald B. Tobias in 20 Master Plots) are a great starting point to help you clarify the story you’re telling.

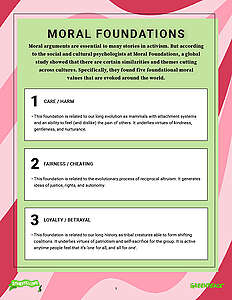

MORAL FOUNDATIONS

Moral arguments are essential to many stories in activism. According to the social and cultural psychologists at Moral Foundations, a global study showed five recurring themes cutting across cultures.

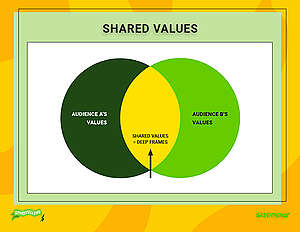

MULTIPLE AUDIENCES & SHARED VALUES

Often we want to speak to a couple of audience groups. In such cases, we might develop specific narratives for each audience. But say that’s not possible. How do we create a story that can appeal to both?

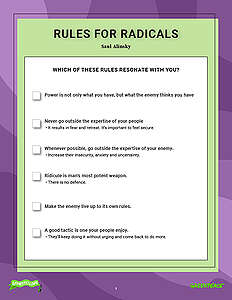

RULES FOR RADICALS

You’re standing up for something that matters to you, your team and community. Here are some salient strategies and tactics to bolster your commitments as you go up against your opponents.

SHOW ME A HERO

The most important thing about heroes isn’t what they can accomplish on their own. It’s what they inspire in others. A hero models qualities that we aspire to, and through their example, we can clarify who exactly we want to be.

SOCIAL MEDIA STORYTELLERS

Every story has a speaker. Sometimes that speaker is easy to identify. They will talk in the first-person or share their individual experiences. Other times, the speaker is hidden. Either way, every story has a storyteller.

THE BATTLE OVER EVERYDAY STORIES

Activism can change the world.

Let’s start with changing its stories.

WHAT DO YOU STAND FOR?

You’re planning your campaign for a reason. Something about the issue resonates with you. It connects with ideals that you hold dear, values that motivate you. What values drive your work?

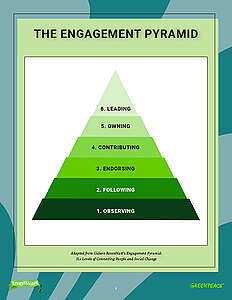

YOUR AUDIENCE & THE ENGAGEMENT PYRAMID

This simple, generative exercise asks you to come up with creative ways to deepen your audience’s engagement through storytelling. Storytelling is, in this light, a campaign tactic.

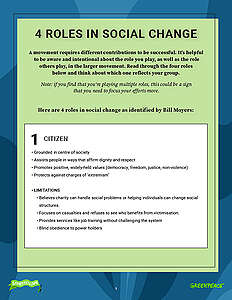

4 ROLES IN SOCIAL CHANGE

Social change happens through a combination of effort and input. Knowing your role in the change you’re fighting for and the role of others can help focus, avoid duplication and use limited resources strategically.

AUDIENCE – 4 KEY AREAS

Begin with these foundational questions to understand your audience.

AUDIENCE SEGMENT

Forming mutually-oriented relationships with our audiences is vital for long-term movement work. Here are some key questions to help us see things from our audience’s perspective.

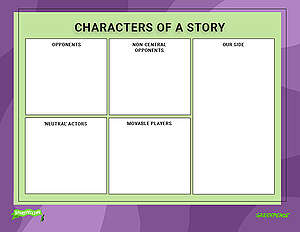

CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

Forming mutually-oriented relationships with our audiences is vital for long-term movement work. Here are some key questions to help us see things from our audience’s perspective.

HIERARCHY OF FRAMES

A frame is how you choose to look at an existing issue. A frame is not right or wrong/true or false, it’s just a specific focus. One issue might have many frames. It’s useful to think of frames and design your frames as a hierarchy from surface and issue to deep.

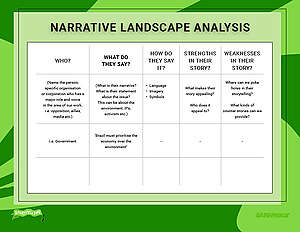

NARRATIVE LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS

We rarely get a blank page as storytellers in the real world. Before we put pen to paper, it’s helpful to map out existing stories.

SHARED VALUES

Particularly when targeting a broad audience group it’s helpful to assess the range of values that exist. Within any group there will be a space of overlap and these shared values can provide the framing for your messages and storytelling.

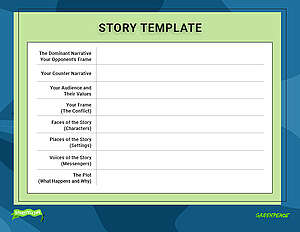

STORY TEMPLATE

Here is a simple template to identify and summarise the basic elements of your narrative. This can serve as a core guideline across all of your story creation work!

THE ENGAGEMENT PYRAMID

A movement isn’t just about accumulating more supporters. It’s vital to cultivate existing supporters so that they become more engaged.

#DROPDIRTYPALMOIL

Even well-meaning people are often predisposed to expect one set of traits and behaviours from men and another from women. Men are more frequently portrayed as strong and courageous, while women are portrayed as caring and nurturing. All of these qualities are praiseworthy, but as we tell our stories, it’s important that we seize opportunities to highlight activists who subvert traditional gender roles and help to broaden the audience’s perspective.

This video is a great example. Its protagonist is Waya, a female activist from Indonesia. Along with her Greenpeace team, Waya daringly rides a small raft out to an enormous industrial ship carrying palm oil and clandestinely boards it. The footage is dramatic, showing Waya clinging to the side of an enormous tanker, determined to bring awareness to the destruction that palm oil harvesting has wrought in her community. When discussing her protest, Waya freely admits the dangers involved, but asserts that inaction would be even more dangerous. The video is not explicitly about gender issues, but by placing a bold and courageous woman at its centre, it weaves a subtle message about equality into its argument against palm oil.

GREENPEACE IN THE ARCTIC AND ANTARCTIC

Two Greenpeace videos, shot at opposite ends of the earth, help demonstrate how activists can use setting to tell a powerful story. In the first, the renowned Italian composer and pianist Ludovico Einaudi gives a performance as he floats on a platform in the Arctic Ocean. The camera provides a dramatic sense of scale, as Einaudi and his instrument appear tiny against the backdrop of the Wahlenbergerbreen Glacier. His mournful notes are combined with the sounds of the great glacier breaking apart and falling into the sea, a result of climate change. This duet is an elegy of sorts. We see a magnificent landscape pushed toward destruction, and feel our responsibility to rescue it.

In the second video, the Spanish actor Javier Bardem ventures to the Antarctic with a team from Greenpeace. Through a combination of images and narration, the video reframes the setting as one that does not exist for humans or their exploitation. Rather, we see a finely-tuned ecosystem struggling to provide for its animal inhabitants, as human intrusions like climate change and commercial fishing disrupt its balance. Bardem and the team of storytellers behind the video make the decision to sideline human characters and focus on the location itself. It’s a daring choice, and one that makes the Antarctic setting a fully-developed character in its own right.

GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL’S STORY OF A SPOON

How do you reach a savvy young audience of urban millennials? With a sly sense of humour! Starting with the dawn of life on Earth, this video propels us forward in time with a series of fast cuts and dynamic visuals. A spirited narrator takes us on a crash course through geologic time, carrying us along as animals are born, species die out and their remains are slowly transformed into fossil fuels that become products that are driven to market. Finally, we reach the crescendo of this billion-year narrative… a guy buying a package of disposable eating utensils. Given all the energy, effort and waste, the video encourages viewers to weigh these utensils’ supposed convenience against their environmental costs, especially when their metal counterparts are so easy to wash. And with the playful presentation and fast pace, the video earns a laugh that helps it spread through social media.

GREENPEACE UK RANG-TAN ANIMATION

This animated video proves that you can tell a moving story in just a minute and a half, and its power depends on its ingenious use of plotting. The basic plot involved is a familiar one: The defence of one’s home. We watch as a mischievous baby orangutan wreaks havoc in a little girl’s bedroom. Frustrated, the girl orders the creature to leave. At the midway point, however, the video takes a turn, allowing the orangutan to offer its own perspective. It turns out that her own jungle home is itself under siege by humans harvesting palm oil. By the story’s end, the girl has pledged to help the orangutan to protect her home.

One of the video’s strengths is the simple plot at the core. We can all relate to the desire to be safe in our own home. But what makes the video especially effective is the clever way it doubles back on itself, using the same plot twice. By first telling a home defence story from the girl’s point of view, the audience is able to quickly understand the events from a familiar perspective—that of another person. They are therefore primed to connect with the plot when it is told from the unexpected perspective of the orangutan. As the second plot mirrors the first, the audience is prepared to offer the animal the same sympathy they offered the girl.

THE FOUNDING OF GREENPEACE

In the fall of 1971, a band of activists set sail on an old fishing boat they christened “The Greenpeace.” The destination: Amchitka, a tiny island at the world’s edge, just one degree of longitude from the line where the Western and Eastern Hemispheres meet. The goal: To confront a nuclear arsenal that threatens both human life and the environment that sustains it. Those aboard the boat were willing to put themselves in harm’s way and use themselves as human shields to protect a vulnerable ecosystem from weapons testing. Though they were ultimately turned back by the US Coast Guard, news of their voyage spread rapidly and helped to reframe both the environmental and peace movements.

For much of their history, those two movements had been understood as separate. But with its very name, Greenpeace has attempted to shift those frames. A planet at risk of war can never be called sustainable. There can be no peace that is not green. This reframing helps the organisation to connect with allies of different activist orientations. By placing two broad issues under an even bigger tent, we believe that we can maximise our impact and help build wide, deep networks of like-minded changemakers.

#PEOPLEVSOIL

First Nations artist and activist Audrey Siegl collaborated with Greenpeace Canada on pair of videos as part of the #PeopleVsOil campaign, and in each, she succeeds in describing the conflict in simple, direct terms that are easy for her audience to understand. In the first video, we get a sense of who Siegl is and what is at stake. She discusses the power of tumuth, a clay traditionally believed to hold protective powers for her community. This immediately establishes a link between her activism, her people and the land that she hopes to protect from the perils of climate change. Then, rather than zoom in on the technical details of her issue, she wisely zooms out to connect her personal conflict to universal values. Siegl creates a dichotomy where Shell Oil stands for greed and evil, and those that resist it stand for community and goodness. It’s easy for viewers to decide which side they’d like to align themselves with.

In the second video, Siegl wore her traditional regalia to confront a Shell oil rig that was being transported to the Arctic. Aboard a small raft, she stands and addresses Shell in no uncertain terms: “You have no consent! You are not welcome!” The visuals are striking. By donning clothing associated with her tribe, she adopts the moral authority of a people who have long inhabited the region and whose home is now under siege. She serves as both an individual with whom the audience can sympathise and as a symbol of a larger struggle. The enormous oil rig, by contrast, appears as an impersonal machine, a tool of exploitation that lacks a human face. Again, the conflict is cast in clear terms, and the audience is left with no question of what team they’d like to join.

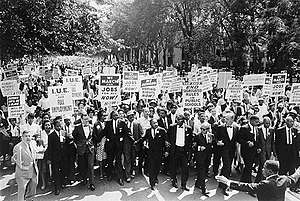

THE US CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

During their many campaigns for racial equality in the 1950s and 1960s, African-American civil rights activists carefully cast both their protagonists and antagonists. The Montgomery Bus Boycott famously began when a woman named Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to obey a law that required her to give up her seat to a white man. Less famous is the fact that local activists chose Parks from among several similar cases in order to launch their campaign. As a middle-aged seamstress who was an active member of her church community, she was able to quickly win the sympathy of a wide range of audiences. Further, Parks was a seasoned activist who had served as the secretary of her local civil rights organisation. She had proven that she had the skills and temperament to withstand the public scrutiny that followed her newfound notoriety.

The movement proved just as strategic in casting its antagonists. During the Birmingham campaign of 1963, activists tailored their tactics to provoke Bull Connor, the city’s Commissioner of Public Safety. Connor was notorious for his virulent racism and disproportionate responses to protests. Activists turned him into their perfect enemy, launching a series of confrontational (but nonviolent) demonstrations called “Project C.” Connor took the bait and instructed police officers to brutally beat the protestors, attack them with dogs and spray them with high-powered fire hoses. The resulting images dramatised the plight of black Americans throughout the South, and are credited with helping turn the tide of public opinion against segregation. President John F. Kennedy memorably said, “The civil rights movement should thank God for Bull Connor.” However, the thanks really belongs to the savvy activists who used his bigotry to their advantage.