An exhibition titled “People Powered Movement vs Shell” uses storytelling tools to uncover the colonial legacy of the Dutch fossil fuel giant. We talked to one of the artists, Chihiro Geuzebroek, about how art and stories can drive engagement for a campaign.

Chihiro, this was your first art exhibition that you curated and produced. How did you come to do this work?

My background is in film. Between 2010 and 2014 I worked on a climate justice documentary project mostly situated in Bolivia, titled Radical Friends. I also work as a public speaker on decolonial climate justice; I make photos and I film actions and have been active in grassroots activism in the past decade. I also do spoken word and write songs such as the Shell Must Fall song.

This summer, Friends of the Earth Netherlands approached Aralez, a decolonial foundation I co-founded, for a partnership to build a pop-up expo on Shell. I jumped on the opportunity and it became a full size exhibition in the process.

How did you determine the framing and the angle you wanted the expo to take on activism against Shell?

It was clear from the beginning that the expo would have a decolonial point of departure. But what does that mean? I had been giving a workshop to NGOs and grassroots organizations on climate racism and in it I had discussed elements of Shell’s past. I knew for the expo I wanted to dig deeper into its colonial origin story in Indonesia and how the biggest multinational of the Netherlands owes its existence to colonial appropriation of stolen land, resources, labor and lives. But I didn’t want to isolate it into the past. I wanted isolated cases of activism to be understood in relation to other moments and movement. So the first installation when you enter the expo presents the earth as a crime scene investigation. It is a web of harm that becomes a trigger for struggle.

Through red lines emerging from the earth and news snippets reporting on different types of harm I wanted to present the scope and the patterns of harm that this fossil fuel company has had on communities. The snippets include articles reporting on how Shell provided luxury toilets only for white workers in South Africa, court cases in Nicaragua regarding harm to workers whose health was impacted by working with toxic chemicals, and how Shell and Standard Oil were involved in arming different sides of the Chaco war to protect their interests in the 1930s. There is a lot of history repeating itself in regards to human rights violations, workers exploitation, racism and pollution. I hope the web we built gives the viewer a more solid analysis of the nature of this corporation, and not just the pie in the sky critique about CO2 particles. I aspire to convey that there is a lot of fertile ground for resistance and movements that have been fighting Shell for numerous reasons, not just climate, in the past 30 years.

What metaphors or motifs did you weave into the story of this expo?

I think one important motif is racism. We found reports of protests in Curaçao as far back as the 1920s. The struggle got more fierce in the 40s and 50s in Indonesia [in Dutch] during the fight for independence. The Dutch Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij (BPM) merged with British Shell in 1907. The British branch was reportedly aided by the UK to draft a law for colonized Nigeria that ensured oil exploration permits were given only to British managed corporations. The Dutch had drafted a similar law in 1899 for the Dutch Indies. Colonial and racist dynamics on the workfloor triggered strikes and uprisings. Today we see many people in the climate movement struggle with how to ‘include’ antiracism, without realizing the struggle against many of these corporations started as antiracism.

Another theme in the expo is workers. Both in Indonesia and Curaçao (another place that has suffered Dutch colonization) workers played a vital role in the resistance. During the anti-apartheid solidarity actions in the 1980s in Netherlands there were reportedly Shell workers taking part in the blockades. I believe in this time and age it is important for Shell workers to see that they have played a role as well in fighting for justice and equity. With expected mass lay-offs, I hope more workers will join the fight for just transition. The expo itself takes place near the Shell Lab in Amsterdam Noord. I am curious if any workers will visit.

And, finally, another theme is the blurred lines between Shell and the Dutch government. We explore this through the news snippets I mentioned, and further into the expo, through walls of photography showing the struggle in Groningen, Netherlands and in Curaçao; plus, through audio stories we produced especially for the expo with activists from Nigeria and Curaçao. So the themes reappear in image, audio and in news form.

You mentioned your primary muscle for storytelling is film, either documentary or short films of activist moments. How was it for you to work with an exhibition floor and use the space and routing as a narrative device?

We only found out last minute we could open in such a big space, so it was quite exciting and challenging to think through spacing and routing. The first rule of storytelling is don’t be boring. The narrative device to help you with that is a balance between advancing and extending. With extending, you engage deeper (zoom in) and with advancing, you move on and create a sense of motion and progression.

In documentary film, you edit your work with post-its on the wall to find the right structure. The post-it map for the expo was more dynamic. Here, I wanted to advance a timeline of resistance. And what I wanted to extend was emotional connection. So after an installation like the web of news—which is very meta, very overarching—I zoomed in by making space to grieve, to mourn the loss of earth defenders like Ken Saro Wiwa and the others of the Ogoni9 who were executed after being framed for crimes they never committed. The great thing about art is that there is space for emotions. Activist organizing often skips over emotions; it’s mostly quite practical and focused on producing impact. But mourning and remembering our elders in resistance is a thing that is both healing and restores our connection to ancestors in the struggle for survival. Creating this space or passage, titled Silence Would Be Treason, honors but also grieves our lost brothers and sisters in struggle.

The fences I used to make this passage of mourning also prevented the viewer from looking further into the space. That helped me bring tension to the experience by not giving away the entire story at once.

Another spatial consideration was playing with height. We have numerous banners and pictures we hung high, so you find yourself looking up and revering activism which is often looked down upon by the media and police. At the same time we placed pictures on the ground, as well as the web of news and rubble from houses in Groningen impacted by gasquakes (earthquakes due to gas extraction leading to soil movement). Here, elements of storytelling are found by the viewer’s feet. The ground or the earth is very much part of the storytelling.

How did you consider using this storytelling to drive audience engagement?

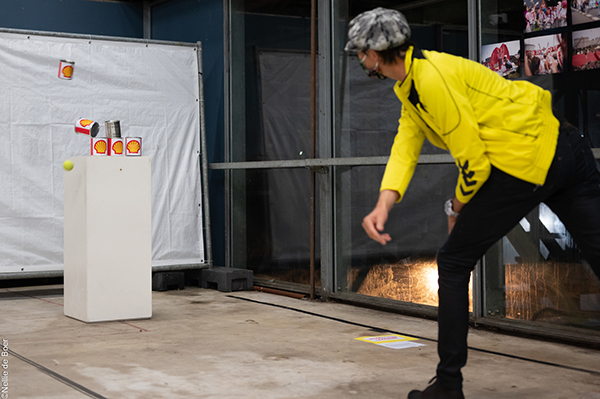

This was fun! We have a piece called Interactive Learning in which you can throw a ball against stacked cans painted with the Shell logo. This game had been previously used in a direct-action and was provided to us as a relic of that. We made a guestbook that invites people to leave their own dream of climate justice. And then there is the Booktable vs Shell where people can sit down, read a little and internalize at their own speed. The booktable also has photography books: one features images of Curaçao and the refinery there; another one shows artistic actions taken by Fossil Free Culture group.

Finally, how did you think through ‘ending the story’? Currently Shell is facing multiple court cases in Netherlands and abroad. In December they are facing trial in the Climate Litigation case. In the case of the Nigerian Farmers vs Shell the case has been ongoing for 12 years. Did you want to end it hopeful or were other matters more important?

In climate justice matters I find hope is often used as a filler or distraction. I wanted instead to end with substance. The final piece is called Dressed for Action and features the Shell-we-stop dress from Extinction Rebellion’s fashion show, a sweater from Shell Must Fall coalition, a bloodstained shirt worn by an activist who was beaten by police during a sit-in blockade against Shell gas extraction in Groningen, and a collection of white dresses used in an artistic intervention against artwashing by Shell. Artwashing is when fossil fuel companies sponsor respectable art institutions to make themself appear more respectable. With each clothing item, we included a picture of an activist moment and a quote. As you leave the expo, there is a table with activist shirts for sale from three different organizations. It is a call to action: even if you do not consider yourself an activist, you can stimulate a conversation about climate justice everyday through something as simple as clothing. Dressing for action is something we can all do. We end the story with DIY… or actually DIT: Do It Together.

The “People Powered Movement vs Shell” exhibit is taking place until December 6th at NDSM-Fuse in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Learn more about the event here. View recordings of the panel on Archive & Activism and on Reclaiming Culture.