Ibram X. Kendi says, “History is calling the future from the streets of protest. What choice will we make? What world will we create? What will we be?”

Anti-racism at Greenpeace must take us beyond Diversity & Inclusion and into our global programme.

“You Trini or Guyanese?” she asked, smiling.

“Trini”, I said, following her gaze to the pair of gold bangles on my wrist. She nodded and motioned me through the metal detector at LAX airport where I was en route to Sydney to start grad school. Patting me down, she mentioned she was Guyanese and her pair was a little different.

Those gold bangles at which airport metal detectors beep in protest are my mother’s gold bera, a traditional piece of jewelry that many Indo-Caribbean women wear. They are tipped at each end with a cocoa pod which, along with sugar, some of my foremothers would cross the Atlantic Ocean from India to spend their lives picking on the plantations of Trinidad, then a colony of the British Crown. The years between 1845–1917 was the period of Indian indentured servitude — a legal loophole created to solve the labour (and profit) problem in Britain’s colonies that followed the official abolition of slavery.

Throughout the generations that followed that era, these bangles became status items and unique cultural markers of the history of Indo-Caribbean peoples. I’ve wondered how and why these stories of oppression and racism came to survive in this symbol: why like this? Why at all? I suppose it’s also a story of fierce resistance and freedom in the struggles against imperial exploits in the Caribbean, a lucrative playground for the ambitions of Spain, France, The Netherlands, and Portugal, too. Tens of thousands of enslaved and indentured people, their children and grandchildren, laboured under the Equatorial sun, yet entertained impossible dreams that freedom would come. Maybe we choose to carry forward the stories and symbols that could be crucibles for the highest vision of ourselves.

Histories like mine infuse the advocacy of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour in the environmental and social justice movements. Generations of these stories, like the threads of spider webs are sticky, curiously strong, deeply intertwined across time, place and peoples. They were woven into the classic liberalism of the nineteenth century that justified capitalism and colonialism. And they continue in today’s globalised neo-liberal capitalist ideologies (‘did we hit our numbers?’) that tell us we must stay on this global treadmill of production, and where ‘good business practice’ looks like environmental destruction and human rights abuses.

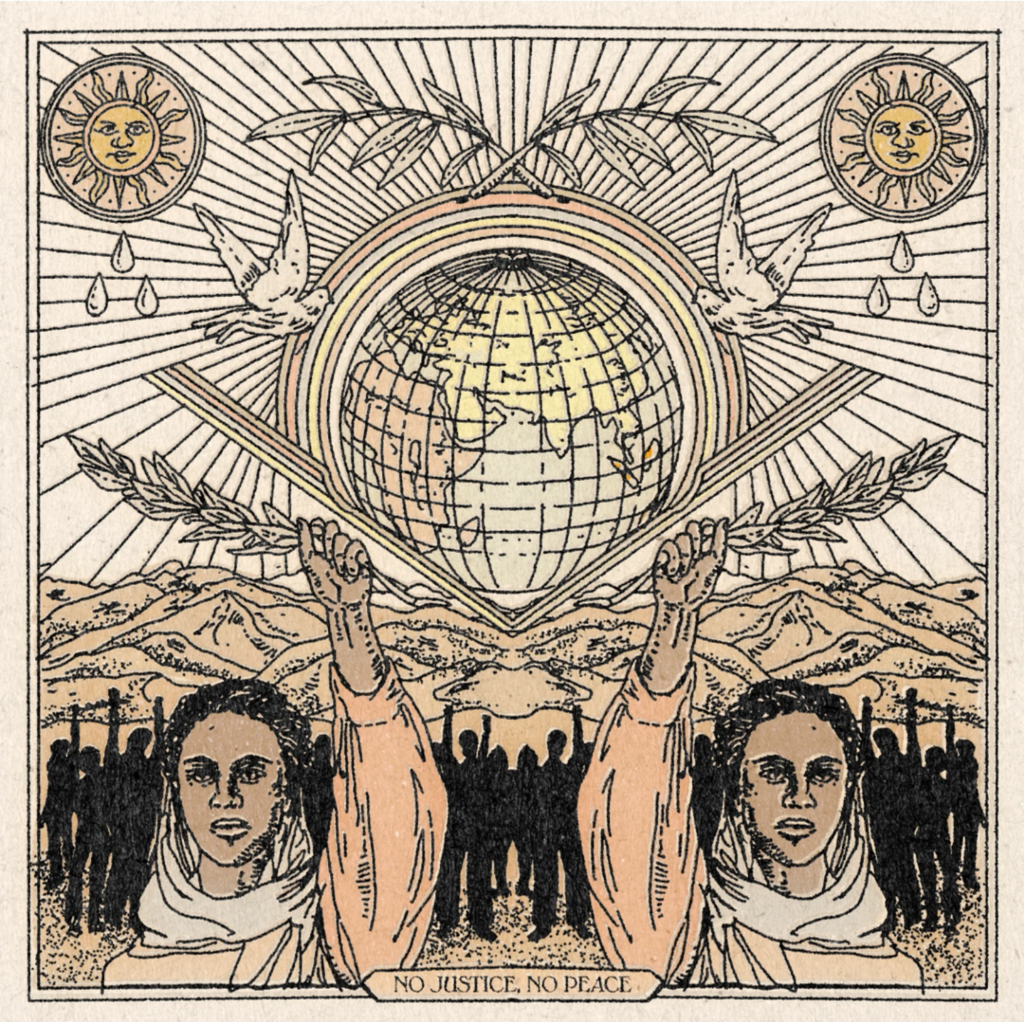

As we witness a rising, global racial justice movement made visible by the killing by police of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man in the U.S, what is now unmistakably visible is that the threads of racism, oppression and resistance to violence and indignity are woven across borders, remain tightly strung and keenly felt in the refrain, “no justice, no peace”. It is no accident that this groundswell is happening amid a global pandemic that lays bare the cruelties of broken social contracts in many countries, and especially for racial and ethnic minority groups who are at increased risk of contracting the COVID-19 virus. Many of the world’s people, including those in wealthy countries, are like Alice, running the Red Queen’s race in Through the Looking Glass: they run faster and faster on the treadmill only to stay in the same place, unemployed or underemployed, and living precariously. It only matters that the treadmill not stop for any reason.

Features not flaws

You can mark the beginning of the physical destruction of the planet, its species, and its life support systems as 250 years ago, when the first steam-powered engine revved to life, or at 500 years ago, when Columbus kick started a race in Europe to acquire new lands and riches. But what is clear in 2020 is that the ideologies and systems built and perpetuated since then have done their work with such brutal efficiency that neither people nor planet can cope any longer.

What we call ‘development’ and ‘progress’ today depended on racism and oppression against poor and marginalised people. The ‘civilising mission’ was a grand project that justified colonialism as the way to redeem the backward, ‘savage’, perpetual child-people of the Americas, Africa, Asia and the Pacific by bringing them into the universal, superior political, legal, cultural, religious, and economic civilization of Europe. But understanding the impact today of these histories is not about the badness of European influence or the nobleness of the colonised and their descendants. It is ultimately the work of understanding and undoing mythologies that still cause harm, especially the mythology of racism — the set of narratives that normalise a hierarchy of peoples where one group is constructed as superior, and others are inferior and their lives disposable.

The past is not yet past

The influence of such mythologies and their ideologies, predominantly those we might recognise as “Western” or “European” (as in, pointing to notions that are culturally specific or historically exclusive to European colonial powers), or that some call whiteness, or white supremacist culture (described by bell hooks as, “a political world that we all frame ourselves in relationship to”), are pervasive and do not respect national borders or tidy historical eras. Racism permeates, perhaps even co-created, modern-day capitalism, which drives the climate crisis, mass extinction, and the ills that concern the broad environmental movement. Othering non-white peoples and countries continues as a necessary project that ensures the cost and burdens of climate change and environmental destruction are borne disproportionately by Black, Indigenous and People of Colour all over the world, and especially in the Global South. This is where the world’s largest corporations pursue bigger profits and escape the tighter environmental and labour regulatory frameworks of the Global North. Today’s global assault on ecosystems is the logical extension of the violence inherent in colonialism and imperialism.

Whether we call it white supremacism culture, whiteness, or something else, at Greenpeace we encounter damaging ideologies in project development when we map narrative landscapes and identify destructive “mindsets”: everything is private property; everything has a price; poor people need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps; economic growth and corporate profit at all costs, and more things will make us happier. The COVID-19 lockdowns in many countries have not only been accompanied by predictable tides of toxic racism against visible minorities, but made the consequences of such ideologies starker, in what work is considered “essential” but which lives are not, and in who could access a social safety net and who has been left out.

‘What you see and hear depends on where you stand’

But many of us in the environmental movement who were born and raised outside the geographic West might encounter these ideologies much earlier in life. They are present when Indian babies are born light-skinned and parents are congratulated for it (colourism). They are present when parents and teachers pressure children to work harder and harder because their talent, smarts and achievements will ensure their success (myth of meritocracy). They are present when we learn what counts as literature by analysing the works of Shakespeare, Chaucer, and Eliot, with one novel or poem by a Caribbean writer, thrown in for good measure. They were present when I moved to Canada and suddenly became a “person of colour” (whiteness as default) and model minority. It would be years before I realised that ‘success’ meant becoming a chameleon of code switch.

Greenpeace, an organisation that emerged in an environmental movement with a history of racism, is embarking on its own reckoning with the children of racist, oppressive mythologies. This is no small, quick or easy feat. Some like Alice Walker take hope in the idea that today, “we can see these problems more clearly in a way our ancestors could not”. Maybe she refers to the wider gaze that is available now, across the span of time, place, peoples, and cultures. As campaigners in 2020, we can choose this perspective to continually examine what our work means as individuals, as an organisation, and as part of the environmental justice movement. Maybe we can see these problems more clearly today because while the violence of racism and oppression have never been masked, more are choosing to take a closer look at its face. Maybe it’s simply because “too much and too little have happened for too long,” as poet Richard Blanco said.

I’ve benefited from the wider gaze of standing on the shoulders of those men, women and children deemed property, endured varieties of structural violence, yet resisted and learned strategies to survive. I inherited a wider gaze from their ways of seeing the cosmos and their place in it, which permeates my advocacy. Religious, patriarchal and caste dogma apart, the rituals and spiritual practices they passed down to carry us confidently across the major thresholds of life tell me that my ancestors participated in a relationship with an ensouled world. They carried Vedic notions of darshan, described by Shephali Patel as seeing the Divine in everything, an image, a place, an animal; a practice, experience and vision that all is One, through the act of bearing witness. But this bearing witness is a two-way street: you bear witness to something alive that gazes back at you, that is interested in your flourishing, too. This was no dead place to claim as private property. And it is a very different entity to a pristine Eden fallen from Grace, no thanks to undeserving humans. It is even a different entity to Greenpeace’s “fragile Earth that deserves a voice”.

Where we came from

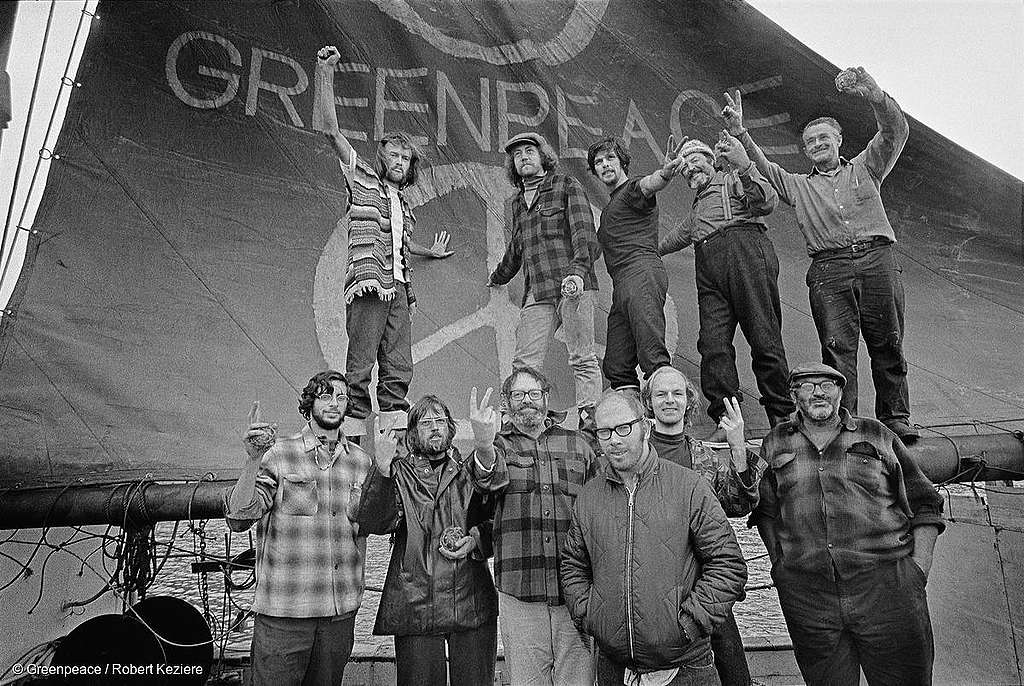

We do not lead single-issue lives, as Audre Lorde said. I did not consciously choose an intersectional environmentalism or environmental justice over the environmentalism associated with Big Green NGOs like Greenpeace. But I didn’t even realise that until I arrived here, and I couldn’t quite slip neatly into the template of ‘ Greenpeace activist’ I saw around me. In the year of its fortieth birthday, a fellow colleague at Greenpeace International gave me a copy of the “Chronicles of Greenpeace”, which was created to mark the occasion. Still trying to make sense of this complex beast, decipher its codes, and unwrap the story that I had chosen (after all, we choose a story when we choose any relationship), the cherished internal myths, narratives, stories, and values of the environmentalism it espoused were on every glossy, 50% recycled, vegetable-inked page: men! (mostly white men); vehicles! (mostly large ships, often referred to as ‘she’ and ‘her’); and the nature! (whales, seals, trees, seas).

More fascinating were whose stories it chose to tell and retell itself. The Warriors of the Rainbow prophecy that Greenpeace’s founders adopted comes from a story in the book, “Warriors of the Rainbow: Strange and Prophetic Dreams of the Indian People”. In one story said to be Cree in origin, a 12-year old boy asks his Great Grandmother, “why have such bad things happened to our people?’ She tells him of a prophecy that someday people from all races of the world will come together to save the Earth from destruction and these people will be known as “Warriors of the Rainbow”, and that the white race was sent here to learn about other ways of being. Whether it was because of its romance, moralism, or indigenous provenance that was apparently trendy at the time, this story resonated with one of the founders, Bob Hunter. He interpreted the prophecy as the role Greenpeace would play, a story and symbol that could be its North Star.

It’s hard to imagine barely ten years later that such a proposal for communicating who ‘we’ are (or adopting a sacred foretelling before securing permission from its custodians) would pass our inboxes without one arched eyebrow. Whether that is because the world has changed so much, or we have new language; what counts as activism and who gets to assume the title has changed; because the composition of the Greenpeace ‘we’ has changed, or people in leadership have chosen to listen, what is clear is that the inclusion of a diversity of voices who decide and define what a Greenpeace story is at any given time matters. To me, this indicates something healthy, a willingness to evolve.

Some say that Greenpeace’s version of environmentalism is new, and that environmental justice — an environmentalism of social justice, located in the needs of marginalised people and planet — is much older, having re-emerged in response to Big Green’s myopic vision of environmentalism (elite defenders of charismatic species and beautiful places). If the pandemic is a portal, as Arundhati Roy says, the Warriors of the Rainbow prophecy brings not merely renewed relevance, but responsibility at this moment in our journey.

Our story today

In the last decade, crises like the COP 15 climate change summit, #MeToo, #TimesUp, certain extreme weather events, the COVID-19 virus, and the recent #BlackLivesMatter global protests, have forced Greenpeace to see its reflection anew, change its work, and how it does the work in fundamental and necessary ways. This was not easy. I remember impassioned debates at many a global meeting about Greenpeace losing its ‘radical’ edge, becoming ‘mainstream’, and whether we should allow volunteers and supporters to help design campaigns that today seem as quaint as old-timey photos. The undercurrent was a fear of giving up power. People are messy, understanding how to engage them is hard, giving up our notions of what we think is best and listening to what we hear is harder. There was a fantasy, too, that we could simply go on as we were and remain relevant.

But we overcame many of those fears. We have better debates than whether ‘mobilisation’ or ‘people power’ is a good idea, or if it is too far from our ‘identity’, so much as how much space and what tools best facilitate people power. The idea of people as change agents — audiences, directly impacted peoples, activists (however defined), allies — today anchor and mould a global programme that relies on their courage. We have built our house on a remarkable faith that ordinary people will say and do hard things when it matters; that they will walk, with or without an institution like Greenpeace, towards their vision for a more beautiful world. We are no hero trying to ‘save the world’, but one amongst many daring to do the impossible together.

We’ve also learned that unless we travelled deeper towards the root causes of climate change and ecosystem destruction, we would be engaged in many more decades of a morbid, never-ending Hungry Hungry Hippos game, trying to stop or delay another company from eating up another ecosystem while another dirty project popped up elsewhere. We realised that we could no longer work with a lens that divided the physical planet into baskets of problems: oceans, forests, agriculture, climate. Our supporters, allies and directly impacted communities are teaching us what a relationship of reciprocity means. We have been willing to go deeper into systemic rot, even when we weren’t sure if we had the right tools or talents to act on what we might find. We sat with that fear, and went ahead anyway.

Between today and tomorrow: environmental justice?

Again and again, we’ve changed our story to write the one we wanted to become. And here lies my hope to shape a global programme that deeply, unabashedly, and genuinely embodies the systemic intersectional lens of environmental justice, which necessarily includes an anti-racism and anti-oppression approach. Environmental destruction and climate change are occurring in post-colonial contexts and beyond, where the drive to develop is unquestioned, unquenchable, in a system that reproduces hierarchy, ensuring certain groups remain outside of a social contract that best protects those already in more privileged positions. This is as true for so-called developed countries like Canada and Australia, as it is for Brazil, India and South Africa. What a hashtag within a pandemic have revealed is the scale, diversity and similarity of the harms, the resistance to impunity, and the longing for a reimagined relationship between people, between people and their elected leaders, between corporations and governments, and between countries.

At Greenpeace, we are again at an inflection point. We can choose to view our programme of work through a wider lens, one that would allow us to see and use our power to respond fully to both the historical and ongoing environmental and social impacts of racism and other forms of oppression against Black, Indigenous and People of Colour wherever we work.

Are we there yet?

Some will say this is a fait accompli. Yes, we have already begun the work in certain offices and in certain projects, like our Climate Justice & Liability Project and the teams that are building our Indigenous Allyship work where an intersectional analysis, including legacies of racism, is more obviously part and parcel of the root causes of climate change and the destruction of land, water, and culture. Anti-oppression and anti-racism also lie openly at the intersection of human rights, international solidarity and climate change. In these spaces, the stories of directly impacted peoples are not used to merely illustrate a problem more vividly as Greenpeace has decided to frame it (a “climate emergency”), but directly impacted peoples frame the problem as they experience it (for example, a loss of identity, culture).

But these spaces are not the norm at Greenpeace. Directly impacted peoples — the “justice” and “peace” ingredients of a more beautiful tomorrow— are too often in the blurry peripheral vision. A constraint that is clearer with every climate emergency response, in the increasing slate of projects that Greenpeace conceives and co-creates with the participation of directly impacted peoples around the world, and in moments of possibility like this one.

Yes, agreements have been made and Equity, Diversity & Inclusion policies created to put our house in order. Upgrading our systems and making diversity and inclusion meaningful, especially in leadership, is the foundation. Yes, we often include some version of the tagline, “a more green, just and peaceful future” or “for people and planet” in our plans. Yes, many Greenpeace offices around the world have generously supported the activities of social justice movements in their countries for many years. But even the current official iteration of our mission and our core values show little, obvious trace of environmental justice, the subjects and agents of which are most often the non-white Warriors of the Rainbow. Yet our values include non-violence (of which, there are many varieties, including anti-racism), and “peace” is in the name. A vision of peace where the goal is collective liberation from violent and oppressive systems that destroy the planet and people, especially those in vulnerable situations, would lead us to different places as we campaign to ensure Earth can “nurture life in all its diversity”.

Yes, in our ten-year Framework, Three Year Objectives and project proposals, I read notions of a vague ‘justice’, and intersectional notions by proxy, like ‘inequality’, ‘equity’, ‘division’, ‘hate’, ‘poverty’, ‘populism’, ‘solidarity’ and ‘culture shift’. But this language looks like strategic inadvertence, or in any case, blanched of meaning. It has even been suggested to me that ‘if it’s in the document, it must exist’, like a term in the constitution of an unfamiliar country I must read into more skillfully. Another version I’ve heard is, don’t worry, it’s there, providing a ‘foothold’ for further exploration. This one is some combination of the former, with an ask for patience, and perhaps a little gratitude.

Walking our talk

It is all well-meaning, of course. But it all lands as a progressive version of “thoughts and prayers”. Racist ideologies that normalise the idea of inferior people and places are still very much alive and at the heart of Greenpeace’s work around the planet. We meet it fighting alongside Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon against the excesses of agribusiness. We meet it in the poor communities living around Manila Bay, flooded by Canadian plastic waste. We saw it in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. It’s in the rising seas around Kiribati, and in the polluted air communities breathe in South Africa.

From the wave of #BlackLivesMatter protests amid a pandemic, we’re more aware than before of how these racialised mythologies of hierarchy birth a racialised kind of oppression woven into the fabric of our lives that continues in myriad forms — government-sanctioned, corporate-driven, and even in the silence of friends.

And yet, what I hear is that these concepts of racism and oppression — the life experience of so many communities of Black, Indigenous and People of Colour around the world (including those in the Greenpeace community) — are a foothold for possible action, one day, maybe, when Greenpeace is comfortable enough and ready to take the step of seeing anti-racism and anti-oppression as vital to the work itself: repairing the rupture of relationships among people and all life on Earth. What I hear is a wish, a warning, certainly sound political and practical advice to be moderate, not to upset the peace too badly, lest our leaders are discomfited by such radical ideas and exercise their privilege to look away.

There is a succinct phrase that my high school English teacher employed for such moments when you’re unsure whether to laugh or cry:

“Jesus, take the wheel”.

“No justice, no peace”

Our global programme anticipates disruption, and 2020 has so far delivered on its end of the bargain, from catastrophic Australian bushfires to a global pandemic and the blossoming of a global racial justice movement. We’ve tried to set ourselves up to better understand and respond to such rapid changes in context, even seismic cultural shifts. So, what will Greenpeace’s response be?

We have to begin by embracing an even wider vision than what may still ultimately amount to ‘wins’ for the environment, and locate these present shifts in collective liberation from unjust, oppressive systems. Otherwise, these moments will pass us by, because they don’t look like we hoped, and we can’t find the ‘hook’ for an environmental organisation. We will struggle to find a place in them, and we will fail to use our power wisely.

We need a reinvigorated narrative of justice and peace. Because while “people power” may anchor our global programme, we do not yet fully account for, or perhaps have a sophisticated understanding of what the justice and peace part of our better world equation actually demands of all of us. An intentionality would not make it so easy to sprinkle “justice” and “solidarity” like word garnish to spice up our programme menu. How could we claim a goal of “system change” without addressing racism and all forms of oppression that push people to the margins and the planet to the brink? How do we proceed to end the age of a predatory fossil fuel industry without tackling racism? What does “justice” or “peace” mean, if not seen and felt through the eyes of the people experiencing injustice?

Any culture shift begins by calling things by their true names. A purported cultural theory of change that fails to properly address systemic issues like racism and all forms of oppression will find tenuous foothold in culture. A programme that tries to address or measure culture shift predominantly via institutional outcomes, like legal and policy change, driven by actors, such as in the fossil fuel or banking industry cannot perform the work of system change, even while it remains critical work. It is possible to enjoy the sunset on the age of oil without making systems change.

This is why anti-racism and anti-oppression, as systemic responses to deeply-rooted, systemic malaise should be seeded into our global programme, where we can help it grow from the roots across the branches of all work we do, inside out,

Are we ready to struggle for systems change?

Some Black, Indigenous and People of Colour in the environmental movement are skeptical that big international NGOs will be able to walk their talk on justice, even as they work towards a “better normal”. That may be because they have seen this movie before: carefully crafted emails from leaders, the flurry to start working groups, to revive conversations and to open fresh Google documents. But they also know only too well that there is no systems change without struggle, and that struggle has always fallen heaviest on the shoulders of those directly impacted. Are we ready to struggle, all of us, to change the structure of the society we live in?

As Angela Davis said, “you have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time”. For now, I remain encouraged by Greenpeace’s intention to listen and to support more robust conversations on racism and oppression. I choose to hear an invitation for colleagues to share how an intersectional lens might evolve a more powerful global programme anchored in environmental justice. With that in mind, a handful of thoughts as we embark:

- A movement in a moment: The global wave started by the Movement for Black Lives amid a deteriorating COVID-19 situation in the U.S tells us that while racial justice and anti-oppression (much like environmental justice) work might look different in each political, economic, social and cultural context, the rot at the centre of interlocking systems of domination that have metastasized over time is not so different. We’re witnessing in their demands for justice the myriad manifestations of how a shattered social contract fails Black, Indigenous and People of Colour around the world: from migrants in Belgium, to poor communities subject to extra-judicial killings in the Philippines, to Aboriginal deaths in custody in Australia, and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Womxn, Girls and Two-Spirit people in Canada. To view this as a moment outside environmental concerns, a distraction in green and just recovery plans, or as ‘an American problem’ would be short-sighted. It would ultimately pin Greenpeace as an outlier, out of touch with the systemic problems of our time, and easily ignored within the movements for social and environmental justice.

- A programme approach: Anti-racism and anti-oppression values should explicitly anchor the systems change aspirations in our global programme. Our strategic commitments on this front must be crystal clear. After all, this is the core expression of how Greenpeace has decided to wield its power to change the world. It should not be boxed into a Diversity & Inclusion issue, but our efforts on the internal culture front can strengthen a programme approach. It means looking with a new lens at our ten year vision and our three year objectives and asking ourselves if the root causes we identified go deep enough, need new expression and clarity in the projects, amended criteria, or require new guidance for the most powerful and relevant campaigns to fully emerge. We must ask ourselves better questions when we look at the slate of work, like “how might this serve the cause of justice, freedom and dignity of all people?” or “how might this address the systemic roots of racism and all forms of oppression?” Such questions will more likely propel improved questions around justice — about who benefits and who is left behind — the kind of questions that are impossible to ignore from collective life in COVID-19.

- Mindset shifts: We have to examine the ways that harmful mindsets manifest and proliferate at Greenpeace and in each country’s cultural context: perfectionism, a sense of urgency, belief in only one right way, either/or thinking, defensiveness, power hoarding, belief in objectivity, that there is only one ‘right’ way and our way is superior, paternalism, feeling a right to comfort over others’ discomfort, and the expectation of burnout, and disposability of activists. None of these serve the goals of mutual empowerment and dignity. What have we normalised that should not be normal?

- The system is where Greenpeace lives, too: We have to identify the naked and disguised harmful ways the global organisation is Euro-centric in its norms about ‘how to Greenpeace’ and how this is pushed onto offices in the Global South where such norms may actively undermine their ability to engage meaningfully with supporters, allies and events in their cultural contexts. If we took an anti-racist and anti-oppression lens to examine project templates, funding criteria, decisions about “priority” status, and who decides what counts as ‘powerful’ work, what might we find? It makes no sense — in fact, it could be harmful — to try to be, say, the German version of Greenpeace in Cameroon or in Japan. We have to work with the values shared with our supporters, go to where their concerns are, and then act on it. What a pandemic has already taught us is that life is still lived at the local level. If our existing programme is viewed through an anti-racism/anti-oppression lens in each country, what would we hear about what “the environment” means to people? What would constitute strategic work and ‘creative confrontation’? What would change about how we do the work, and with whom?

- The struggle begins with each of us: When we built our story around “a billion acts of courage”, we probably didn’t have a billion acts of discomfort in mind. But anti-racism and anti-oppression is a personal, maybe lifelong journey of unlearning and relearning. Comfort is not in the definition of courage, but ‘coeur’ (heart) is in the root of the word. Whether we choose to protect others or our own egos, and sit with the discomfort of unlearning may be moment by moment choices, and we will get it wrong. But as Austin Channing-Brown reminds us, anti-racism work is nothing less than the work of “being better humans to other humans”. As the Hermetic saying goes, “as within, so without, as the universe, so the soul”.

- The vision is green and just and peaceful: “Green” cannot be colourblind. It goes without saying, but a greener world does not necessarily lead to one that is more just or more peaceful. It may be technically possible to achieve a greener world (or country) without tackling the systemic rot of racism and oppression— with better technologies, science-informed laws and policy. The UK broke its record for coal-free generation during the pandemic, but the injustice of the Windrush scandal came to light and is ongoing. Many celebrated clear blue skies over Beijing, but China’s Black immigrants faced racist abuse. If we have halted carbon emissions, unfurled clean energy everywhere on Earth, and “solved” climate change, but some Rainbow Warriors cannot go for a jog without fear of the police, we have not solved climate change.

- Independence and integrity: We are a politically and financially independent organisation, but many of the funders of international non-profit organisations like ours who influence what we work on are located in the Global North and relatively conservative. We may have to educate some of our supporters on why anti-racism and anti-oppression work is both necessary and strategic, and bring them on the journey with us. For other supporters, we may not be walking far or fast enough.

- Leadership and support: It goes without saying that Black, Indigenous, People of Colour should lead this work, but the choices of many not to get involved should be respected. A seat at the table has a price, and it is a kind of labour of a different quality to that which comprises job descriptions. Unfortunately, it may come with personal risks, especially for women, colleagues who are in less senior positions, on contract, or from Global South offices. And frankly, some may rather be applying their talents than having these debates. Support and care for our colleagues in the ways they wish to be supported is crucial.

Toni Morrison noted three responses to chaos: violence, stillness, and naming/renaming. People around the world are tearing down the stories too long forced on them, naming the wounds, and renaming things too long called ‘heroism’, ‘civilisation’, ‘progress’. Because of them, a new collective story of the future is being written now. Some governments and some groups are responding with violence. Stillness is necessary to critically reflect on what this means, and to lay robust foundations that can hold tomorrow’s possibilities. But paralysis and performative action cannot be an option.

Wherever Greenpeace works, it can wield its power in this rewriting of a vision of dignity for all people, and of the sacred contract we have with all life on Earth. The decision to do so should not be radical, but the transformation must be. But we can do hard things. I have seen Greenpeace build a crucible for a new story of courage, compassion and hope to blossom. I believe it’s big and sturdy enough to hold a Greenpeace that might draw closer to the one of my vision: where the word “intersectional” does not preface environmentalism.

History may be calling from the streets, but the future is on our doorstep. The eternal questions revisit Greenpeace on the ripple created by George Floyd’s murder:

What story will we choose to write from here?

What choice will we make?

What world will we create?

What will we be?

At the end of the day, it is who we become that changes the world.