There is a story that strikes me as an important one this week, as we slip into the season of reflection, celebrate International Human Rights Day, and observe the unfolding COP 25 climate conference; as we look back at all that has been accomplished by those who came before, all that is being done today, and all that there is still to do in the task of a greener, more just, and more peaceful world.

It is Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen’s powerful Jewish story of ‘the birthday of the world’. It was gifted to her for her fourth birthday by her grandfather, a student of kabbalah. As she tells it, our world came into being as a great ray of light from the heart of the holy darkness, the source of life. By way of an accident, the vessels containing the light of the world shattered; the wholeness of the world was broken. The light scattered into a thousand thousand fragments, and although it remains hidden, it is held by all events and all people. Her grandfather said that the humanity is a response to this accident: we are here with a task to find this hidden light in people and events, to make it visible, to restore the world’s innate wholeness. This task of restoration, “tikkun olam” is a collective one, for all people who have ever been born, all people currently here, and all people yet to be born.

“What does ‘justice’ mean’ to you?”

At law school, we learn (quickly) that justice and law are really two different rivers that don’t always meet. In the justice system, ‘justice’ is separated into procedures (state-owned and led processes engaged in towards an outcome — if you can afford them). And the much stickier question of its substance, what justice means — who defines what is fair or ‘just’, where do we look for it, what does it look like, how do we get it, how do we know when it’s been done — is open to all kinds of responses depending on who you ask. The justice ‘system’ cannot be solely relied on to do the timeless, unending work of bending the moral arc of the universe towards justice.

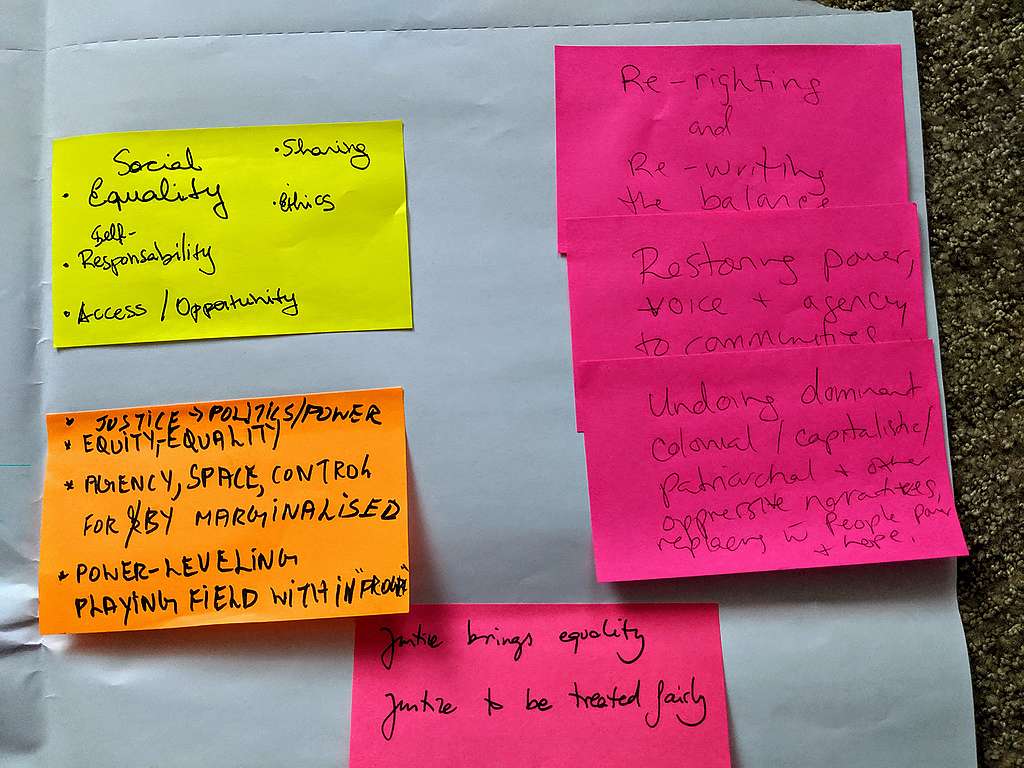

Today, I see more and more Greenpeace teams campaigning within and alongside diverse streams of social justice movements, from human rights to indigenous rights, to protect civic space as much as forest ecosystems. So, I recently posed the question, ‘what does justice mean to you?’ to colleagues from around the world who work in a plethora of geographies and disciplines, from science, law, and communications to campaigning with forest communities, on creating ocean sanctuaries, more liveable cities, and climate change policy. We were in conversation about how some of us in the core team of the Global Climate Justice & Liability Project think about ‘justice’, and the role of stories and storytelling play in mechanisms for seeking justice, inside and outside of courtrooms.

Their responses were rich, varied and unexpected:

‘To be treated fairly’.

‘When everybody has equal rights and equal opportunities in all aspects of their life’.

‘Re-righting and re-writing the balance of power’.

‘Reweaving the torn fabric of our humanity’.

‘Giving people what belongs to them’.

This idea of a restoration, a giving back of what already belongs, but may have been taken away resonated with another powerful idea of justice by American writer and activist, Darnell Moore: ‘what is possible when we realise that we belong to each other’, re-imagining a politics based on a refusal to leave anyone behind.

That sounds like one possible answer to Aristotle’s age-old question of what it means to lead a good life. But it also suggests that some part of the meaning of ‘justice’ might be located between people, what we believe we owe each other in order to live well together. Stories and storytelling can help us reveal and negotiate these intricate questions around justice — if we choose to listen generously, even though we might disagree on the ingredients of a ‘good life’. Storytelling has always sung to life the work of social and environmental justice, and continues today in new ways and spaces.

But first, what is ‘narrative’, ‘story’ and storytelling?

Narratives can be loosely thought of as ideologies, ‘myths’, even ‘mindsets’ imbued with our beliefs and values. Master narratives are the big, dominant narratives operating at a societal level that unify and define what kind of behaviour or aspirations are ‘normal’, ‘acceptable’, and ‘right’ in that place. Some of them are destructive: ‘more material things will give me more status, power and protection’; ‘immigrants bring problems’; ‘without fossil fuel companies, our economy will crumble’; ‘better technology can save us from climate change’. They’re like invisible belief systems; they’re contested, and they’re constantly in flux.

Master narratives are not neutral; they have real world ramifications for people, especially those in already vulnerable situations (they often serve to justify treatment of these people). They can dramatically shape what and how much some get to have experience in life; some of these fear-based narratives are even ossified into laws. Much of the work of social justice movements has been interrogating and breaking apart harmful narratives.

Story is a way of seeing the world. We could see story as a series of events that happened, and the meaning we take away from those events, or ‘how the world works’, according to us. When we tell a story, we’re involved in the work of making meaning of events, for ourselves, for others. We’re often involved in the breaking and remaking of destructive master narratives, undoing the dangers of a single story. Sometimes, we do that by offering new stories that can give new meaning to what we see.

Why does storytelling matter in social and environmental justice work?

“Liberation is always in part a storytelling process: breaking stories, breaking silences, making new stories. A free person tells her own story. A valued person lives in a society in which her story has a place.”

— Rebecca Solnit

Storytelling, like the work of justice, is always about power, because it’s about making conscious choices: which characters are centred, whose fate matters and what are they up against; who is the narrator, what points of view will be included; how the central conflict or problem is named and framed, and what events are included and excluded cue what solutions are likely; genre and plot choices tell the audience what kind of story this is, the possibilities for where it might go, how it can end. It is in the telling that an unquestioned ‘reality’ held by the audience might be broken apart and reshaped by the choices we make in storytelling.

For many people, especially for the people whose realities are not ordinarily heard or seen within mainstream cultural narratives, to tell a story can be a bold, inherently political act. To tell, share or amplify another story than the ones we usually know is to dare to illuminate other truths, to dare to be believed, to believe transformative change can happen, to believe that people can make change. The history of movements for social justice have been about breaking silences.

What’s the purpose of stories in the work we do?

As campaigners, we tell stories for so many reasons, and each of our campaigns are an exercise in story-making, a new story of what could be becomes possible each time a new campaign launches. But storytelling’s real work is about shifting power, whether it’s through big, global public campaigns, targeted political lobbying, strategic legal actions, or non-violent direct activism. Storytelling itself is one theory of change working alongside others to engage with change agents, audiences, and allies in walking towards a vision of a better world.

We tell stories to inspire, to move, to persuade. For much of its recent history, the modern, Western environmental movement has heavily relied on rational argument in a bid to move people to act. We broke natural systems into their component parts — forests, oceans, soil, glaciers, atmosphere, wildlife— and explained what science said was going wrong with them. But physicist Werner Heisenberg provocatively remarked, “what we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning”. Science requires our interaction with what it investigates. Scientific knowledge is a self-correcting narrative we build from the world as we experience it evolving together.

Science remains fundamental, but the ways of engaging with and communicating what’s happening are changing.We’re starting to centre different forms of knowing — people’s experiences of how those natural systems are changing — as knowledge in itself. Over 2018, during its groundbreaking investigation into the responsibility of 47 ‘Carbon Majors’ into climate change-related human rights harms, the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines’ heard from typhoon survivors, indigenous peoples, farmers, fisherfolk, alongside civil society members, academics, lawyers, scientists and policymakers to gain a broader picture of the impacts of climate change on Filipinos. The stories of those whose lives are impacted by climate change gave substance to what ‘human rights harms’ look like in the Philippines. Their stories now form part of what is presently the largest repository in the world of scientific data, documentary evidence of climate-related human rights impacts, and legal analysis that led to the Commission’s finding that the fossil fuel industry can be held morally and legally liable for climate harms. This was a historic moment for the Filipino petitioners who dared to bring the complaint, and opens a new chapter for the climate justice movement. But these stories are also helping to cement new narratives: climate change is a human rights issue and businesses, especially Carbon Majors must respect human rights.

We tell stories so that they might become public knowledge — from where to find water in the desert, how the universe came to be, who to avoid, and what happened by those who survived — stories help us name what happened, illuminate big, complex systemic problems through the eyes of the individual, making it possible to widen and deepen our understanding of injustices by ‘bringing the trouble home’. Stories that become public knowledge have a role to play in moving us towards what might happen next in the long, hard and necessary work towards restoring what has been broken.

We tell stories to disrupt destructive and false master narratives that are taken as true. As Elie Wiesel warned, “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere.” We can interfere with new narratives, by giving the space we have to the stories of voices yet unheard. Through storytelling, we can point to the underlying broken systems and corrosive narratives that drive environmental destruction. The beauty of storytelling is that a good story, whether visual, spoken, watched or read, is felt before it is known (this has good and bad consequences).

We tell stories to spark the law into life. Before their historic legal victory over the right to their lands this year, the Waorani people of the Ecuadorian Amazon literally rewrote the map and the narratives about what lies under their forest home with their stories, to harness the power of the law to protect their homes. Resource concession maps are not concerned with sacred sites, turtle nesting grounds, the relationship between the trees and the rivers — what is priceless and precious, for whom, and why.

We tell stories about our vision of a more beautiful world. We know that we need a story of where we’re going and what is still possible amid the stark and daunting realities of climate change, a reminder as that from Alice Walker to “Look closely at the present you are constructing: it should look like the future you are dreaming.”

James Thornton, founding CEO lawyer of environmental law firm, ClientEarth says we need a new story to direct our attention towards the long term, one that can channel our energies and diverse efforts, a motivating story of our shared future that can hold and allow a spectrum of solutions to emerge, including those that new jurisprudence makes possible.

We tell stories to connect across our professional silos, to stand in solidarity, and sometimes, new and necessary narratives are born. At the first Peoples’ Summit on Climate Rights and Human Survival this year, people and groups working on issues traversing human rights and environment civic spaces around the globe issued a declaration on climate justice, affirming a unified commitment to work together. But they are also committed to building a new narrative that interlinks the work of human rights and environmental advocates in a new way not yet seen, one that says people have a right to a safe and stable climate.

We tell stories — we ask for stories — to give and take courage, strength and to stand in solidarity. Stories generously shared by human rights advocates and environmental activists shine a light on why they choose to take action, what gives them courage to keep going, what they fear, and what needs to happen next. As Filipino environmental lawyer, Tony Oposa says, “it is said that if you want to be heard, you tell a story.” And sometimes, it is just enough to know that you are not alone.

We tell stories to share what goes on in places most eyes don’t see. We tell stories to share the magic and beauty, of the places and things we love and would fight for, to begin conversations, to spark curiosity, to unveil the mysterious and the marvelous. Visual storyteller and oceans activist, Cristina Mittermeier reminds us that even if we live in cities, we all have a sacred ecology, places and ways that we relate to nature around us that are special.

We tell stories for their power to make us visible to each other, in a way that facts, maps and statistics can’t achieve on their own. We need to where the bushfires are and how much land is burning. We need to know why they’re happening, and who is to be held accountable amid the din of the political circus. The stories of what it means to the people who call that place home and those on the ground help us to better understand what and who is at stake, to place what is happening in the wider frame, as the first step towards taking action.

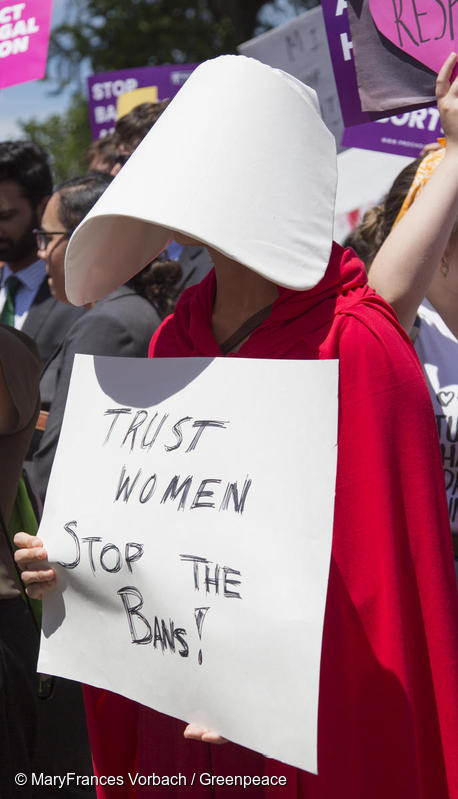

We go to stories to locate ourselves in the unfolding story of now, for metaphor and language when the plot looks frighteningly familiar: how perilously close we might come to Offred’s world in the Republic of Gilead if we allowed silence and comfort to set in.

But more importantly, we go to stories to remind ourselves of our power, of what is still possible. As Neil Gaiman said in his novel, Coraline says, “Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten”. If Hogwarts students can defeat Death Eaters, then maybe students can defeat the NRA.

Storytelling and justice are interwoven threads

In the work of campaigning, stories — the deep listening, as much as, maybe more so than the telling — can become a doorway to a shared reality, where it becomes possible to engage in what is unfair, what is out of balance, in rewriting and re-righting wrongs. Storytelling and our work in seeking justice, whether in courtrooms, boardrooms, on campuses, in city streets or on seabeds, does not mean that one automatically leads to the other.

But storytelling as a social technology holds unique potential to build empathy, for interrogating the idea that if we do ‘belong to each other’, what would that mean; for understanding that the work of reweaving the torn fabric will take all of us. Storytellers do the work of speaking to injustice, of speaking truth to power, of standing for what is at stake, which makes restoration possible. Stories make visible what work remains to be done.

For Dr. Remen, a takeaway from the story of the birthday of the world is that each of us is here on Earth because we are exactly what is needed, at this exact moment in time to do the work of restoration, of justice. What a new way to look at the power we can wield day to day. Maybe the task of tikkun olam begins with storytelling, with listening to ‘what justice means’ to those we hope to engage. Maybe it can lead to better questions, like “what could my work mean for ‘justice’?”